The OODA loop, reaction time, and decision making

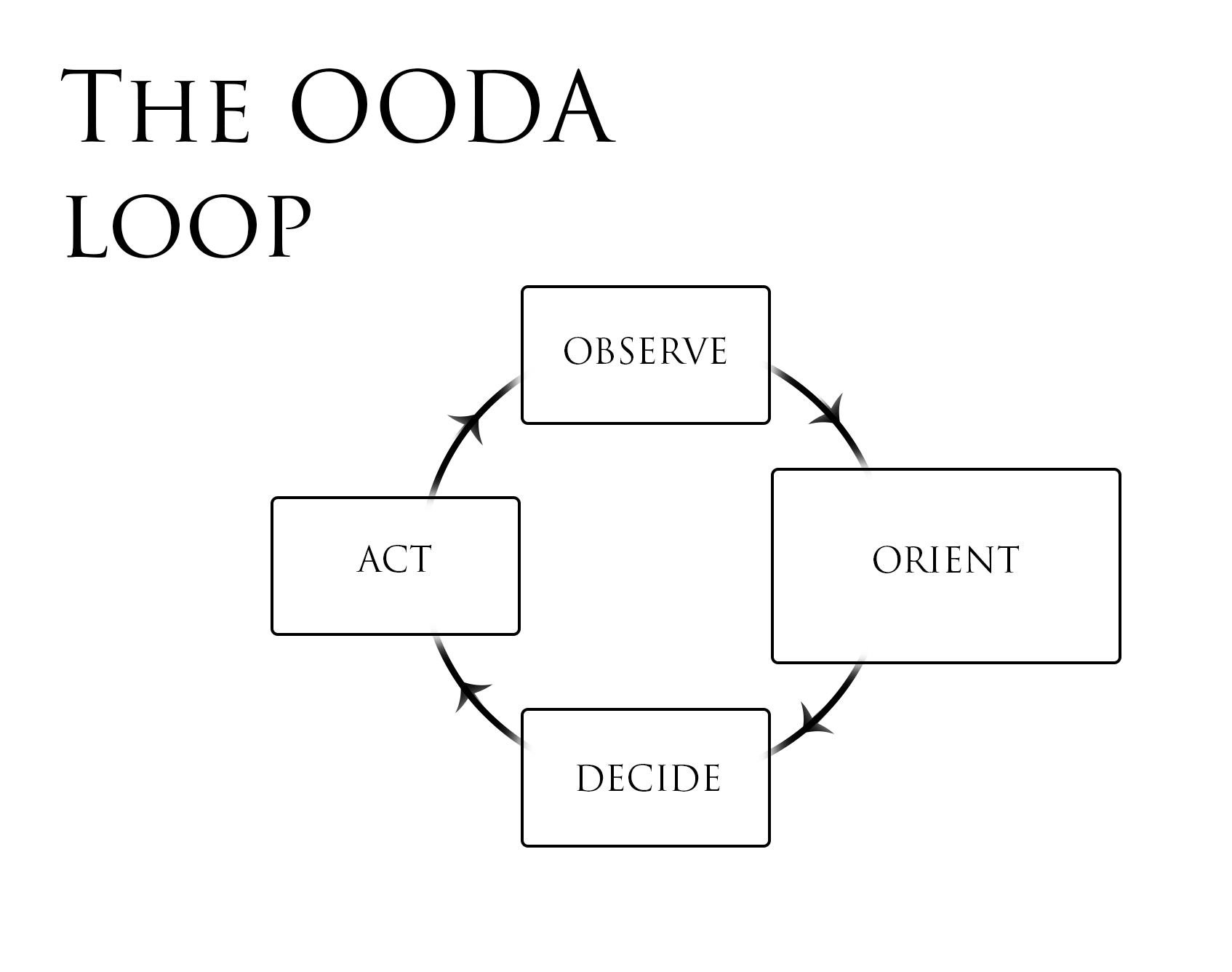

Since the mid-19th century, human reaction time and decision-making have been popular research topics for experimental and cognitive psychologists. In the 1950s, Air Force Colonel John Boyd borrowed from this human-factor knowledge as he developed his Observe-Orient-Decide-Act (OODA) loop decision-making model. In this article, we will explore how these dynamics contribute to tactical decision-making by law enforcement officers who are “forced to make split-second judgments in circumstances that are tense, uncertain, and rapidly evolving.”

The OODA Loop and Combat

The most common reference regarding Boyd’s cycle addresses the need to “get inside the opponent’s OODA loop.” In other words, the individual who cycles through the OODA decision loop the fastest will likely prevail in combat. This acknowledges that the opponent also has an OODA loop. The OODA loop, boiled down to its essence, analyzes, synthesizes, and defines the most critical component of human performance – reaction time.

While the OODA loop model is a conceptual strategy for combat, and while officers need to be prepared to use reasonable force up to and including deadly force at a moment’s notice, the preferred approach is to “talk” suspects into compliance whenever possible. According to the International Association of Chiefs of Police, approximately 99.96 percent of the time, officers are successful in doing so. Therefore, a more global view would be to view the officer’s job as “managing” the opponent’s OODA loop when practicable. In fact, this is precisely what SWAT teams do during critical incidents, and the vast majority of such events are resolved peacefully using the Time – Talk – Tear Gas strategies that ensure the safety of both suspects and officers.

A Real-Life Example

In October 2010, an undercover Seattle police officer was assaulted during a downtown narcotics operation. One of the suspects fled into a convenience store, where he was followed by a second undercover officer with a firearm in hand. As witnessed by the store clerk, the officer was verbally directing the suspect to get down on the ground. While the suspect apparently raised his hands in a “surrender” position, he failed to comply with the officer’s commands. The officer advanced on the suspect, kicked him in the thigh, then grabbed him by the back of the head and pushed him to the ground. The officer then kicked the suspect two more times (falling to the floor after he did so) before a uniformed officer came to his aid and handcuffed the suspect. The video in question is available here.

Forensics and Timeline

Using a frame-by-frame analysis, we can determine the timing of the encounter with a fair degree of certainty. From the moment the suspect begins to raise his hands until the officer’s kick makes impact, 2.7 seconds pass.

The gross timeline:

- 0.0 seconds: The suspect begins to raise his hands.

- 0.4 seconds: The suspect’s hands are up.

- 1.3 seconds: The officer is moving through the store’s doorway.

- 2.2 seconds: The officer initiates the kick.

- 2.7 seconds: The kick strikes the suspect’s leg.

V. Analysis of the OODA Loops

Officer’s OODA Loop

- Reaction Time and Decision-Making: If we apply a reasonable 0.25 seconds to make the decision to kick, then the officer (consciously or unconsciously) decided to execute the kick at approximately 1.95 seconds of the timeline (2.2 kick-initiation mark minus 0.25 seconds). Or, looking at it another way, he “decided” to kick 1.55 seconds after the suspect’s hands were raised.

- Motor Program Initiation: Once a decision to initiate a motor program has been made, it is difficult, if not impossible, to inhibit the action. In other words, at the 1.95-second mark (0.65 seconds after moving through the threshold), the decision to kick was made, the motor program initiated, and it was likely now “fire and forget” – with limited ability to turn back.

Suspect’s OODA Loop

- Initial OODA Loop Cycle: It appears that the suspect first notices the officer approximately 0.65 seconds before he begins to raise his hands. The movement of his hands then takes 0.4 seconds. Therefore, we can estimate that his first OODA loop cycle took about 1.05 seconds.

- Response Time to Comply with Commands: Research by Jason has indicated that the average time for an individual to go from a standing position to a prone position as rapidly as possible is 1.1 seconds. Using that time frame, we can estimate the response time for the suspect to comply with the officer’s commands to get on the ground as follows:Reaction Time (RT) + Movement Time (MT) = Response Time 0.75 seconds (RT) + 1.1 seconds (MT) = 1.85 seconds (Response Time)

The suspect is also processing a stressful situation wherein he is listening to a set of commands while simultaneously processing the fact that an individual with a gun in his hand is rapidly closing on him. Additionally, he is likely attempting to work out some way to avoid his growing reality of being the focus of this officer. All of this consumes mental bandwidth and eats up the suspect’s response time to the officer’s commands.

The final inquiry is whether the suspect would have had ample response time to comply with the officer’s commands before he would have been kicked. Let’s assume the suspect decided to comply and go prone at the moment the officer cleared the threshold. Remember, it takes the suspect 1.85 seconds to go prone. Going back to the officer’s timeline, from the moment he cleared the threshold until he landed the kick, only 1.4 seconds had passed.

As you can see, unless the officer would have been able to stop his kick after having already launched it (an unlikely premise), it is likely that the suspect would have been kicked in the face or torso rather than in the leg. It appears that the only way the suspect could have avoided the kick would have been if he began to get on the ground even before the officer entered the store. Perhaps he should have done so, yet I am not convinced that he could process the information that rapidly.

Tactical Considerations

A. Alternative Actions for the Officer: From a commonality of tactics perspective, going into the store was a tactical entry. While this was certainly “hot pursuit” of a felony suspect, this was not a hostage rescue or an active shooter/killer situation. If, before he entered the store, the officer was able to observe that the suspect had put his hands up into a surrender position, and if the officer could orient to the fact that the suspect was surrendering, or perceived him as doing so, the officer may have decided to act by stopping at the threshold and giving commands to the suspect. By holding at the door, the officer may have been able to wait for backup instead of entering alone, and therefore may have avoided the struggle (with an apparently non-resisting suspect) where he stumbled and fell to the ground while holding a firearm in his hand, exposing everyone to the threat of an unintentional discharge.

Best Practices and Officer Safety:

While we would be remiss in rendering an opinion without all the facts, we can certainly use this event as a discussion and learning point about “best practices.” However, a final caveat: Just because lesser intrusive force or alternative methods of making an arrest might have been available, that fact alone does not make the officer’s decision per se unreasonable.

Conclusion

While it may seem that I am simultaneously defending and criticizing the officer’s actions, I am actually doing neither. My intent is rather to promote an intellectual and academic discussion. Let’s share experience and expertise and have a productive debate to develop and enhance methods to best keep officers, citizens (and suspects) safe. Please let’s avoid the “he deserved what he got” viewpoint.

First, that doesn’t meet the standards of our profession. Second, whether he was involved or not, the suspect was acquitted of the crime. Finally, part of “keeping officers safe” is ensuring that we as trainers do our best to keep them out of jail and out of a federal civil rights suit. This officer had been charged with a misdemeanor assault as a result of this event.

Epilogue

Luckily, the expert who first opined that the force was excessive changed his opinion after having the opportunity to read the officer’s report (with the useful lesson to us all to avoid reaching conclusions without all of the information). At that point, all charges against the officer were dropped.

Conclusion

In summary, this article has explored the OODA loop model, its application to law enforcement, and the critical role of reaction time and decision-making in high-stress situations. By analyzing a real-life incident through the lens of human factors and OODA loop dynamics, we can gain valuable insights into tactical considerations, best practices, and officer safety. Engaging in intellectual discussions and avoiding premature judgments are essential for enhancing our understanding and improving training methods to protect officers, citizens, and suspects alike.

FAQs

- What is the OODA loop? The OODA loop stands for Observe-Orient-Decide-Act and is a decision-making model developed by Air Force Colonel John Boyd in the 1950s. It analyzes the critical components of human performance, including reaction time, in rapidly evolving situations.

- How can officers manage a suspect’s OODA loop? Officers can manage a suspect’s OODA loop by providing adequate time for the suspect to perceive, decide, and respond to commands. This can be achieved through tactics such as holding at a threshold, allowing for backup, and using verbal commands to facilitate compliance.

- What factors influence a suspect’s response time to an officer’s commands? Several factors influence a suspect’s response time, including reaction time, movement time, processing of stressful stimuli, mental bandwidth allocation, and the ability to comprehend and comply with commands in rapidly evolving situations.

- What role does reaction time play in an officer’s decision-making process? Reaction time is a crucial factor in an officer’s decision-making process. Once an officer has made a decision to initiate a motor program, such as a kick or a strike, it becomes challenging to inhibit that action due to the body’s natural response mechanisms.

- Why is it important to avoid premature judgments in analyzing use-of-force incidents? Premature judgments should be avoided when analyzing use-of-force incidents because they can lead to biased conclusions. It is essential to consider all available information, including the officer’s report and the totality of the circumstances, before forming opinions on the reasonableness of an officer’s actions.